Bad People

Patrick Nathan

By then, Monica was primed to see the dog as salvation. She still considered herself a scientist, but she’d begun to believe in signs. The market had collapsed and it was cheaper to own than to rent. Meanwhile, her landlord had defaulted. Her lease, up that October, would not be renewed. In the eviction letter, the bank included a phone number for those who needed help finding a new apartment, but no one ever answered it. Some force had taken its turn, rolled its dice, and there Monica went, one two three four: purchase a home at four percent interest in a low-income neighborhood.

This is yours, she’d thought as she unlocked the front door. As winter set in, she couldn’t remember the last time she felt rested, but the house belonged to her. To be able to say those words was an opportunity and she’d taken it, preciously.

“This is financially wise,” she huffed as the first snowfall covered her sidewalks and the small, formidable rhombus of driveway off the alley. It was a kind of mantra, to centre herself and throw one shovelful after another over her shoulder. This was her responsibility as a homeowner, as a person in her community. It could even be exercise. Her chiropractor suggested a gel pack she could freeze or microwave. She purchased a more serious shovel—wider, with a steel blade at its tip like a safety razor. She felt powerful. But power was only a chemical in the brain, and other chemicals, she learned, could break it apart and devour it the way alkaline compounds, to use a familiar example, ate at fats until each dissolved into ooze. She could barely straighten her body out on the floor. You are an adult, she thought as she iced and heated and iced until neither felt different from the other. An adult who’s made the biggest mistake of her life.

It was time to be deliberate. She returned the gel pack to the freezer, opened a five-dollar grenache, and arranged herself with a blanket on her couch. She caught the stars of this constellation with a wide-angle selfie. A cozy night in! she captioned it, with an illustration of two anthropomorphic hearts embracing. Every few minutes, someone noticed she was alive. No one asked who the other heart represented.

Her favorite places went on without her, in that old neighborhood—the coffee shop, the pizza place, the bar with the cheap G&Ts on Tuesdays. She felt shut out and made lists of places near her house—her home, she reminded herself—which could fulfill the same functions. A brunch place, a place for a quiet dinner, another for impromptu drinks. Nobody joined her. Crossing the river was too far. It must be time, she reasoned, to spend less money at restaurants, to eat healthier. At home she made quinoa with butter and broccoli and looked out the front window. It was a wet winter and it kept snowing, as if to punish her. She wondered if it was legal, instead of shoveling, to simply call out – Be careful! – whenever someone walked in front of her property. A warning like this should absolve her of liability. I can’t shovel, she might tell some bureaucrat. Here is a note from my chiropractor. I live alone. I’m in constant pain.

These thoughts arrived in the hours the sky spent darkening. They were, unfortunately, ideal for shoveling, as there was no sun to melt the bottom layer of snow, the part she could never scrape up. Slush was particularly threatening, as it was only future-ice, and ice was what you never wanted—not out front, not on the roof, not in the gutters. Ice could ruin you. She’d once dreamt of ice entombing her, prying apart the siding and the shingles and shattering the windows as it swelled in the night. She lived in a poor neighborhood where poor people left early for their bus stops. With their boots, they flattened the overnight snow first thing in the morning and left an impenetrable, compact crust. Stay away from my house, she tried to tell them, telepathically, as she clutched her mug of tea. It was so plain to her, how every neighbor and dog walker and child was not only contributing to her pain, but how they could expensively hurt themselves and, in their vengeance, cost her everything. They would turn her into one of them.

She began to recognize them, these neighbors and dogs and children. One man used her mailbox as a garbage can. Children tossed pastry wrappers and juice boxes into her yard. A few times a week, a teenage boy parked his car out front and let it idle, his stereo shaking her windows as he disappeared for an hour at a time into the house across the street. Monica knew what he was doing to the girl who lived with her grandmother, and she felt so unbearable about it that she went out to her own car and thought, Let’s go, and didn’t.

How had things gotten so bad? There was no one left to ask. She used a wooden spoon to knead the knots beneath her shoulder blades. It only antagonized her pain. Was this the universe? She looked at her bank account, her mortgage balance. Soon she’d make more money, or have to. She was more than qualified to be a senior engineer, and just think of all the products she would formulate with that title, with those resources. She thought of the products. The company would at last appreciate this gem of theirs, Monica in the lab, for launching their new cleaning line in time for next year’s holiday season. It would revolutionize, she imagined, their position in the industry. Every day, she stood on her anti-fatigue mat and wore an ergonomic strap that pulled her shoulders back, and people pitied her. At lunch she savored the notifications from friends who called the photos she posted of her clean and orderly house beautiful, tidy, cozy. No one ever came over. It was never a good time. But she should be so proud of herself. A house! they all said, just like that. A house! It would really be worth something.

*

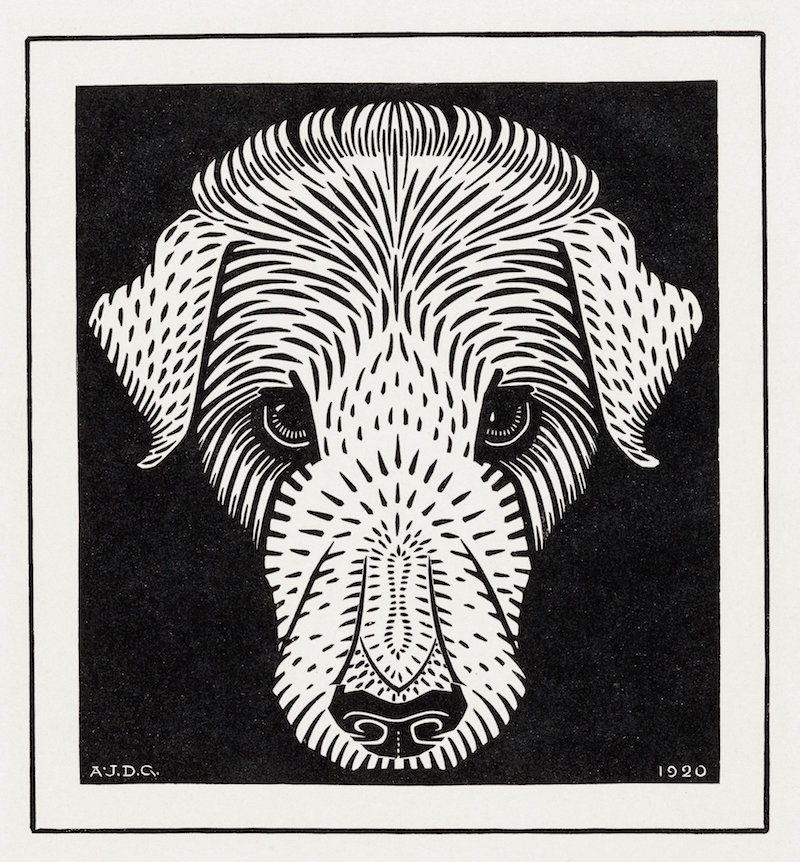

Monica found the dog one Saturday morning, trembling in the warm spot beneath the dryer vent. Her tag said Lois but the phone number had been scratched out. It was unthinkable to leave her, where she’d only shake like this until she died, so they sat together in the living room and grew closer until Lois curled up next to Monica, and Monica too began trembling. Lois had a heartbeat. She breathed in and out. Her body, beneath her damp and musty fur, was warm. For Monica, it had been so long that she cried. Together they went to the pet supply store in her old neighborhood, where she saw familiar strangers she’d missed seeing, smelled the random weed she’d missed smelling, and bought enough food to keep Lois alive. They would try to make this last. But on Monday morning, back at her bench, all she could think of was Lois, alone at the house. Lois too would watch the neighbors and come to recognize them, resent them. Monica went home sick.

That evening, she wrote a public post under Lost and Found. Lois misses you. Adorable and well-behaved shih-tzu found cold and hungry. Please contact me as soon as possible so she can go home. She left her name and phone number and the nearest intersection. One man called and said she sounded sad in her post, but very sweet and young. He had no information and it wasn’t his dog but he’d like to help. She thanked him and later edited the details so she was M, not Monica, and deleted the word adorable. Nobody called. Monica sat with Lois and took pictures with her. They watched movies. Lois loved stop-motion animation and sat poised on the floor, directly beneath the screen, and followed the characters with quick, comic twitches of her head. Monica had nightmares where Lois was brought to her door by a neighbor, some awful person she hated, broken and crushed, cut into pieces, tortured, blinded, burned. “I may have to kill myself if your owner ever calls,” she joked with the dog, and laughed as Lois licked the tears from her face.

“Do you even remember him?” she asked. And it was this assumption, him, that made her feel ashamed. She put Lois on the floor and sat with her head between her knees, a trick she’d learned somewhere, or almost learned, to feel some way or fix something, to get well. That was it. She wasn’t well. “I’m not well,” she told Lois.

*

The message from Ty arrived a week later. Monica was adjusting to the idea of living with Lois when this awful voice came crackling through her phone, a tear in her universe. “I miss Lois too.” He wanted to meet up, in public if they could, and give her some cash as a reward. “Not a lot, sorry, but it’s what I can do. The least I can do. Thank you so much. Please call me back. I miss my baby.”

He hadn’t sounded Black on the phone, and Monica didn’t like that she noticed this. They met at a coffee shop in her old neighborhood, where she tried to feel welcome but instead felt fraudulent. Ty wore a sweatshirt and sweatpants. When he stood to shake her hand, she could tell, with alarming clarity, that he was circumcised. Had she always been this terrible?

People nearby called Lois sweet and beautiful. They touched her chin. It was none of their business. Ty thanked them all the same—and so, embarrassingly, did Monica. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I guess we’ve grown a little close.”

“She does that,” Ty said. He had a familiar look. He too was someone who lived with a great secret pain, even if it wasn’t physical, not exactly. It felt ridiculous to separate them anyway, this pain and that. Lois looked up at him, and from her eyes, he noticed, it seemed as if she’d already forgotten, that she’d already forgiven him.

“Here is my number,” the girl named Monica said. “Just in case you have any questions or if anything happens, if things change.”

“I already have your number,” Ty said. Lois’s heart was once again beating in his hand, right where his palm joined up with his fingers. It was back, and he felt special for noticing this, as if he were a boy or man who loved uniquely, who wasn’t like the others. “But thanks. That’s good to know I guess.”

*

Normally, when they drove together, Lois sat in the passenger’s seat and looked calmly at the city. There was nothing excitable or foolish about her; she had an uncommon dignity. But there must have been a lingering mistrust, despite the forgiveness he’d seen. Lois refused to stay on her side of the car. She curled up on his lap as he drove back toward his neighborhood. His shitty neighborhood, he always called it. “I’m so sorry munchkin,” he said as she lapped at his chin.

Ty lived with Lois in a garden studio. Its lone egress window faced a busy sidewalk, and on the rare days he bothered to raise the blinds he saw boots, jeans, sweatpants, pajamas, sneakers, stolen shopping carts, cigarette butts, windborne trash, and countless dogs. Every few nights, a raccoon crawled out of a nearby storm drain and descended into his window well to scratch at the screen. He’d never fed it but it’d clearly developed the idea that he should. In the morn-ings, when his car engine turned over, he whispered “Thank god.” Whenever he parked it, he tried to make it look like a car you’d want to steal. He wasn’t proud of this, of any of it—living on boxed pasta and microwave breakfasts, stealing dogfood by “accidentally” leaving it on the tray beneath the cart. His trashcans overflowed with burger and burrito wrappers and he jumped whenever he heard a police siren. He never brought anyone here, and never would.

Over time, something had happened to his skin that seemed undoable. He ran every morning, even in January, and did push-ups and crunches and squats until he was nauseated, until he trembled. But he was no longer that person, that body. In pictures, he no longer looked like what he’d grown used to, and because of this he no longer offered himself to others.

The apartment he and Daniel had shared had been Daniel’s to begin with, and so of course Daniel kept it and all its things—things that had also, for years before they’d met, been Daniel’s. Aside from his clothes, some movies and books, and a game console, Lois was the only part of their life together that Daniel insisted Ty take with him. She had been Ty’s idea, a creature to bond over, and for two years they had loved her together.

Early on, Ty punished himself by driving back downtown, near Daniel’s loft. There, he took Lois for long walks along the river, where he knew Daniel went running after work. They never ran into each other. He couldn’t tell if this was intentional, if Daniel had fore-seen such a childish plan, or if it was merely something, he told Lois, “in the stars.” Ty had become someone who believed in stars, even if he couldn’t take them seriously. These days, he only went downtown if some date invited him to the bar or to his apartment, someplace clean and high up, even if that meant the men who fucked him looked at him with a certain sense of adventure or wondrous pity. Luckily, there was Lois to call him home, and no one ever had to humiliate him by asking him to leave.

They were only together again, he and Lois, for two days before Monica left him a voicemail. He knew, instantly, what she wanted. “It’s silly to get so attached to a dog,” she said, “but it wouldn’t be a long dinner. I’m just thinking something simple while Lois hangs around with us, some linguini and some wine, a movie, I don’t know, never mind, I’m so sorry.” When he first met Daniel, there wasn’t much of a physical attraction. They’d flirted together online but he was just another man, another beautiful dick. His fawnings had assigned meaning to Ty’s body, this thing he’d cultivated for others to enjoy. It was only after Daniel kept inviting him over, as the flings added up, that Ty came to appreciate Daniel himself, his beauty, his kindness, his sheets, the view from his loft, his sense of humor.

He called Monica and said yes, dinner would be great, and she was very sweet for thinking of him, and Lois would be so pleased.

*

Much has been written, and more said, about the goodness of dogs. In a film I watched recently, set in France in the 1960s, a man is rowing down a narrow river at the edge of a village. He is only scenery, part of the provincial backdrop to a serious, adolescent conversation between two hormonal characters. On the bow of his boat, a dog—I couldn’t tell you what kind—stands at attention, surveying the water and glancing back now and then at the man as if to ask, Is this right? Is this good? Shall we go on? A dog wants to be good; they have a moral compass. We sometimes say “Good dog” and “Bad dog” in response to the actions of specific dogs, but this is not what I mean when I say that dogs are good. No dog is bad, not in the way we sometimes decide a person is bad. I don’t think this is a phenomenon unique to dogs so much as it is to human beings, and I don’t mean this in the way you will initially read it to mean.

Monica had cleaned, or at least it seemed that way to Ty. But then everyone’s house or apartment was clean compared to his. “My hole is immaculate for someone who lives in squalor,” he’d quipped with a hookup not long ago, fishing for a nice gift or a ride home. Lois knew her way around Monica’s house and he followed her, as if she’d elected to give him a tour. “I painted this room to feel summery,” Monica called from behind. The kitchen looked hot. “It didn’t turn out,” she admitted. Lois sat on the floor until Monica gave her a bowl of water. She scratched her behind the ears.

Ty was surprised by his jealousy.

The house itself was enormous and empty. Its rooms existed in different tenses. “This was the parlor, I think,” she said, “and this over here will be the library, once I find someone to build the shelves. I was thinking I could do it myself but my back—it’s just always giving me so much shit.” She poured wine; she had a cabinet in the dining room—a whole dining room, off by itself somewhere—filled with three vintages. “I buy a case of each. It’s like getting a free bottle.”

Maybe she really did need Lois more than he did. After all, it was Ty who’d abandoned her, who’d left her outside to die.

“I don’t want you to think I have a lot of money,” Monica said as she served spaghetti. Was he supposed to connect this—spaghetti instead of the promised linguini—to what she’d said? She looked so ashamed, and he supposed he did as well, generally. “I mean I’m not showing off, or not trying to. I live cheaply but smartly is all I’m trying to say. Jesus, shut up Monica.”

“It’s okay. I don’t have any money either. Who does?” He laughed, even though Daniel had money, which meant Ty, too, at least for a while, had had it—or had access to it. There was a period in his life where he could take a credit card to the outlet mall and not worry about it, even though he’d always worried. He’d always pictured Daniel picking through his statements, asking what this or that charge was for and could he see what Ty had purchased. He’d never asked. They’d never discussed it. It had never mattered at all. To Daniel, money was worthless.

They only made it twenty minutes into the movie before Monica folded herself up against him. He could feel her waiting and he didn’t know how to get out of it. As he turned his head he thought he would say “I just broke up with my boyfriend,” but her mouth fell slightly open—just open enough. He followed the steps carefully and marveled at the softness of her face, and was perhaps more patient than anyone she’d ever been with, if being was what this was.

“Fuck, that’s huge.”

“Ha, thanks.” It was a compliment he was used to, but not from a woman. It made him feel decorative and controlled instead of envied and admired. It had been a long time—since high school—since he’d done this. Men were so much easier. He liked everything they did to him and how quickly they did it. He liked how they felt, how they smelled. Now, he’d lost all initiative, all confidence. They both stared at it as it throbbed, as it waited for something to happen to it.

“Here,” she whispered. “Let me. Do you w—”

“No.”

She stopped, one knee on the couch and the other bent above him, halfway to a straddle. Instantly they were different people. It felt like they could laugh it all off, if they did it now, but it wouldn’t be a lengthy opportunity, and in fact was passing now, it was too late. Monica stood and gathered her clothes and disappeared into a far room. Ty’s body was very dumb and very male and it pulsed with a desire to stay and apologize, to get rid of all this tension, but he knew he couldn’t. Lois watched him dress. “If I leave you here now,” he whispered, “you’ll never trust me again.” Of course, Ty wasn’t the kind of person who deserved forgiveness, who should be trusted. Sooner or later, he thought, everyone would know that. Everyone would know he was a bad person.

*

Monica had known her error before she’d made it. It was dormant in her and went hot, as if it were a memory of her own, as soon as she’d asserted her desire. Something in Ty had gone dead and this rejection was only her fault, entirely hers, for a fraction of a second. But that was long enough for the hurt to eclipse all compassion, enough to wound him. And now he was gone. “You could have said something,” she joked with Lois, who seemed by some tacit transfer to be hers again, to belong here and to live with her. She’d cried when she found her in the living room after Ty had left, and felt terrible for her own gratitude, for having won this precious prize. She hadn’t heard from him all week and was afraid to message or call. “You could have told me,” she said again, as if Lois would at last acknowledge it, would chortle with the almost-laugh dogs tend to have, somewhere in the middle of a sneeze and a cough and a little growl.

She was humiliated but no longer felt rejected. Ty was prob-ably out there feeling used, feeling raped. Do men feel that? “He’s telling people what happened, that he met this girl who tried to rape him,” she told Lois. Because his friends were gay—she assumed—they would all understand and commiserate. She would be, to them, such a straight woman. This is why they don’t trust us, she imagined telling Lois, who did, it must be said, understand questions of trust, and would have perhaps appreciated this opportunity to articulate her own perspective, to share her own wisdom, had dogs evolved a little differently.

Lois’s affection felt different now. That feeling of being chosen was no longer there. For the first time, Monica used a voice to put words in Lois’s mouth, high-pitched with an unplaceable accent: “Because you feel guilty.”

And Monica nodded. “Yes,” she said, in her own voice. “Yes, you’re right.”

“You should apologize.”

“You’re always so real with me.”

With Ty’s phone number, she was able to locate his account. Rarely did he post anything public—profile photos, mostly, and the occasional “life event” that signified a graduation or a new job. He seemed to work at a gym not far from her house. His most recent photos showed him alone, but those slightly older showed him with a man, an older man, and in warmer seasons that no longer felt possible this deep into winter. It seemed as if this had been love, or at least something to mourn now that it appeared to be gone. She poured another glass of wine and tried to learn more. In the shadows of her imagination, she understood why men would like a man like Ty. Lois had stopped to rest on her bare feet and was breathing against her. Monica grew selfish as she clicked through what she could of Ty’s life. “You’re being crazy,” she made Lois tell her, but ignored these warnings. She felt flustered and swollen and thought Ty should have gone through with it, what was it to him, for only a few minutes, just to get it out of her mind. His cock had wanted it, and weren’t their cocks supposed to get what they wanted?

Stop, she thought. This wasn’t who she wanted to be, even if it was who she really was. She tried to click away but in her haste, her shame, noticed that she’d instead requested his friendship. Before she could cancel, he accepted. He’d been there all along, oblivious to being spied on, and it made Monica feel like she’d been watching him shower from a hidden cupboard. And it was all so immediate; it had all changed so quickly. Ty was now, by some definition, her friend. He had no idea what kind of person he’d decided to trust.

*

They agreed to meet in their own neighborhood, now that they both knew it was theirs, at a coffee shop neither loved. Here, no one knew them, or Lois; no one presumed they could pet her or speak to her. She sat calmly between them, under a small table by the window, as they apologized and defended themselves. Ty’s wrists were bandaged and Monica knew she couldn’t just ask. She hadn’t meant to make him feel uncomfortable, she said, to pressure him; he hadn’t meant, he responded, to lead her on. It was just loneliness. They were both so lonely. Neither had anyone left, anyone who cared. Her house was too big for her and his apartment was like living in a grave. Their lives had become so terrible and so quickly that there was nothing to reach for, nothing to grab onto as each plummeted. “He was our whole life,” Ty said in a strange voice of his own. Monica realized it was his own interpretation of Lois, his own shadow he spoke to when they were alone. He touched, with an unusual tenderness, his new wounds.

It wasn’t true, Monica assured Lois. “No man is anyone’s life.” Which of course she didn’t believe. Here was a man, after all, whose friendship would save her, would give meaning to her life. Something in her mind was crawling out of the dark. Even before she proposed it, she knew, immediately, that she would never be able to tell him how much she still hoped, how the fantasy hadn’t gone away. Having him in the next room would be a way to nurse it. She was ashamed to be so manipulative, but not ashamed enough. Besides, it wasn’t as if Ty weren’t formulating his own scheme—all that space, all those nice things, that privacy. The unburdening of having to do everything, to be everything, all by yourself. They could use each other and no one would get hurt by it, no one would have to lose.

“I do have a proposal,” Monica said, and Ty felt Lois at his feet, her tail slapping against his calf as Monica made her pitch. Lois understood him better than anyone, and she seemed, he thought, to approve. It could be, he mused—and he even told Monica this—one of those pairings you see on TV, the fag and his hag (no offense) living together and supporting each other and never having the temptation, he said, that others might “in our situation.”

As long as he got to keep his secret, he thought. As long as Monica could never know how close he’d come to drowning Lois rather than abandoning her—at which point he’d have killed himself for real. You couldn’t live with a terrible thing like that, which is perhaps why he’d let her go instead. Logically, then, Ty had wanted to live. How had he not seen this until now?

She saved both our lives, each would say of Lois, never quite telling the other how true it really was. It was the story, the tale, they told everyone—once they began to meet people in this new neighbor-hood, once these new friends began saying things like, “Let’s all meet at Ty and Monica’s.” How they’d met through Lois, how Lois had brought them together and taken care of them, how she approved of their achievements as they grew older and she aged rapidly alongside the last days of their youth. It was really Lois’s house, they said—“She just lets us sleep here.”

It wasn’t until Lois was very old and had trouble negotiating the stairs that they no longer shared this story. The tale was no longer so inspirational, harder to convince strangers or even people they’d known for years what a fortuitous difference a dog could make in a person’s life, especially with such an old and deaf dog lying there on the rug. This was salvation? Everyone had become a skeptic. But she was good to the end, Lois, even if Ty and Monica were not. They’d never imagined they could be, that they had it in them. They clung instead to what they believed they were, all those years, despite Lois’s every attempt to convince them otherwise, despite the goodness she saw in them. Lois believed that people could be happy, that they could tell and remember and cherish happy stories about their lives. Ty and Monica were the only friends she’d ever had, and for her entire life on this planet she had tried to convince her friends that this is how you could be happy, this is the kind of story you wanted to tell about yourselves and each other. Because of this, Lois would’ve wanted me to stop this story here, where she still lived among love—a word I’ve tried not to use loosely but is left vulnerable in my vocabulary, as it is in anyone’s, to a craving, even a deranged need, to believe in what all dogs believe.

Click here purchase the issue in which this piece originally appeared, or subscribe to receive all future issues as soon as they're published.

You can subscribe to our infrequent newsletter here: