A Case History of Graphomania

Helen Charman

Let me first outline an imaginary scenario.

A thirty-year-old woman is infatuated with her colleague at the university. Temporarily unaccommodated—she sleeps in her office, in a sleeping bag on top of a thin duvet on the crunchy carpeted floor—she has no clear direction in which to progress this desire. In a meeting, under the bored and therefore too-perceptive eyes of her more senior colleagues (she’s new and she’s a fixed-term employee; everyone is her more senior colleague), she mentions a book to him, offhand (or at least, she thinks she’s being offhand). The book is, amongst other things, a theorisation of desire.

Alone in her office, bored and twitchy, she decides to do something that, on balance, does feel insane. She wants to lend him the book, but she doesn’t have a copy with her (most of her belongings are in a storage unit in a city four hundred miles away, where she used to live). The book is hard to find: she wants a specific edition, yellow and pleasingly smooth, with a painting by Charlotte Salomon on the cover, but the book is about to be reissued in mint green and white, which is worse or, rather, is not exactly accurate to the book that she wants to give him. She goes to one of the two large bookshops in the university town; they don’t have it. She goes to the next one, browses for a while, can’t find it, decides to ask the woman at the counter. They do, she says, they have one copy, upstairs, in ‘Biography’.

Back at home, which is to say, back in her office, she decides rather than simply give him the new book, she wants to read it. As she reads it—and she has read this book many times before—she finds herself overcome with the urge to make notes in it, notes she can feel rising inside her, struggling to get to the surface, notes, in fact, that she has already made, in her other copy of this book, the last time she read it, or maybe the time before. Unable to ignore this insistent prompting, she reads the book in a feverish mode of productivity, covering its pages in the quotations she remembers it bringing to mind before: ‘for Lacan, love at first sight is a form of attack that suddenly overpowers the subject’; ‘Said, on Così Fan Tutti: ‘Every affirmation, every instance of truth carries with it its own negation, just as every memory of love and conjugal fidelity also brings with it the danger and usually the actuality of something that will cancel it, annul it, obliterate it’; and, on the final page, a line from George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda that has come to feel like a miserable personal prophecy, ‘as if some ghastly vision had come to her in a dream and said, “I am a woman’s life”’.

She puts the book in his pigeonhole, which is in a room under constant surveillance in the complex of buildings in which they both work, eat lunch every day, teach students, and have coffee (and, of course, where she illicitly and in fact illegally sleeps). She bumps into him on the stairs, feigns collegial indifference, disavowing any ulterior motive in the book, reminds him it’s not a gift but rather, ‘it’s a lend, a lend!’ This is true. The object—rewritten, re-conjured relic of her earlier readings, recreated at the impulse he inspires in her—is not for him but simply towards him, pointed in his direction. She wants it back.

*

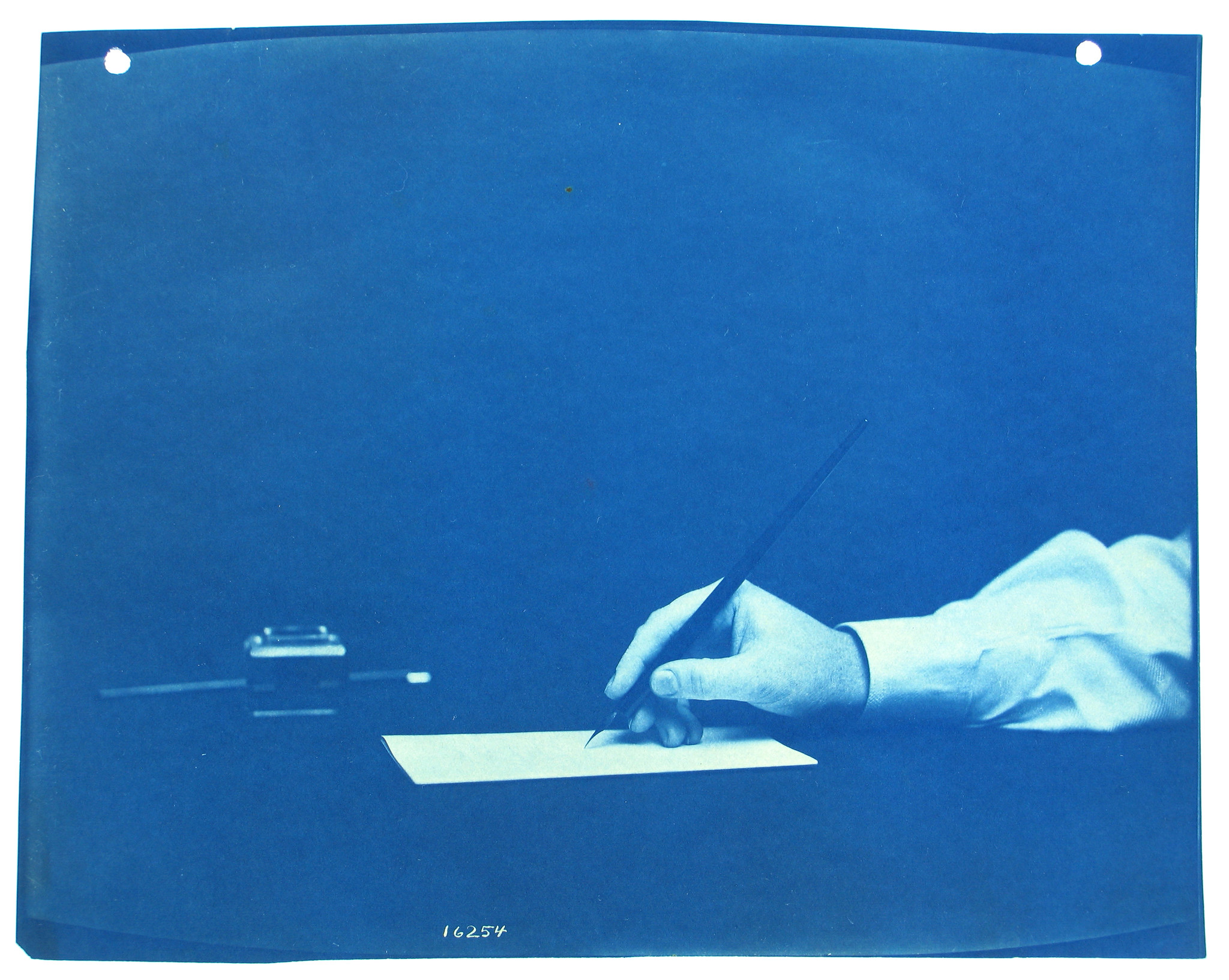

Desire drives people mad. Madness, historically, has sometimes driven people to write. Graphomania is a term with a hazy history. Its first recorded usage was in 1840: in a specifically psychiatric context, related intimately to graphorrea, logorrhea, and hypergraphia, it refers to a condition in which a patient feels compelled to produce reams and reams of text. Max Nordau defined it, in 1895, as intimately related to artistic ‘degeneration’, being as it is ‘the condition of semi-insane persons who feel a strong impulse to write’; Milan Kundera related it specifically to the desire to publish, to ‘to impose one’s self on others’ (what is a love letter, if not this?). Wayne Kostenbaum, writing in 1994, distinguished graphomania from its sibling, logorrhea, by drawing a line between the levels of abjection inspired by speech and text: logorrhea, for Kostenbaum, is the most ‘resonant’ of the two terms ‘for it reflects revulsion at flow, and revulsion at the speaking mouth. Displace the horror onto the hand, and then we are in the territory of graphomania’. To believe in logorrhea, he continues,

you must believe in sexual desire’s glamour, and in the possibility of desire turning into death and loathing. To believe in logorrhea you must still believe in sex: must fear it, worship it, wish to exorcise it. You must believe in the possibility of over-excitation, promiscuity, loss of control, loss of the self’s borderlines.

If the case history of this graphomaniac teaches us anything, it’s that the woman’s annotating hand still retains some belief in sex.

To write compulsively and unrequitedly towards the desired subject is to desperately and against all the odds bring a form of communication into the world, kicking and screaming, pulled up from the grave and forced to march around the streets of the living. For some, this has been definitional of love itself: Roland Barthes, in A Lover’s Discourse, diagnoses it as a state marked by the compulsion to address those who are absent. ‘You are gone (which I lament), you are here (since I am addressing you)’. Anahid Nersessian, in her gloss of Barthes in Keats’ Odes: A Lover’s Discourse, reminds her readers that for Barthes, this is a version of Freud’s game of fort/da, in which his infant grandson taught himself to bear temporary absence with a cotton reel. ‘But,’ Nersessian writes, ‘if love is an invitation to act out—to drift into habits of ambivalent attachment left over from childhood—it is also an invitation to refine language ad infinitum’. To rewrite, in other words, onto writing itself.

What if you never drifted away from those habits of attachment in the first place? Adam Phillips, reading Freud’s romance of early childhood, writes that the process of growing up is a process of relearning desire:

Being realistic is a better guarantee of pleasure; it is an injunction to want sensibly. The child may expect the earth of himself and others, but if he grows up properly, he will begin to want something else. But what happens to wanting when it isn’t wanting everything, and when it isn’t wanting what one wants? Or, to put it another way, from an adult point of view, as it were, how do we decide what a good story about wanting is? And which stories will sustain our appetite, which is, by definition, our appetite for life? Even to want death you have to be alive. Morality is the way we set limits to wanting; the way we redescribe desiring so that it seems to work for us.

It doesn’t matter how many times I return to the Freud that Phillips is writing about (1920’s ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’), or to later theorists of attachment like D. W. Winnicott (another favourite of Barthes), when I read that ‘injunction to want sensibly’, I always feel guilty, found out, startlingly apprehended, even identified: I have still not learned this lesson. I do not want sensibly. Indeed, embedded as I am in a life in which I—miraculously, even if precariously and unevenly—make all my money and spend all my time teaching the study of literary texts and writing about them, I am also furnished with an ever-expanding collection of textual artefacts that offer me instruction in such irresponsible wanting, and—even worse—show me how to write it into being myself. Later in the same Adam Phillips book, which is called The Beast in the Nursery, he quotes from the literary scholar Northrop Frye’s book about William Blake: ‘nearly all of us have felt’, Frye writes, ‘at least in childhood, that if we imagine that a thing is so, it therefore either is so or can be made to become so. All of us have to learn that this almost never happens, or happens only in very limited ways; but the visionary, like the child, continues to believe that it always ought to happen’. So, too, does the graphomaniac. If you write something into being, it might come true.

There is a poem by Louise Glück—it is called ‘Elms’—which begins with a perfect pair of lines: ‘All day I tried to distinguish / need from desire’. In most interpretations, for Glück’s speaker, who has spent the day ‘looking / steadily’ at some elm trees, the ‘twisted forms’ of the tree trunks are a metaphor for the process of writing, and writers are ‘the builders, the planers of wood’, who can’t grasp the understanding that ‘the process that creates / the writhing, stationary tree / is torment’. But what if the writing—the symptom—comes from the very fact that need cannot be distinguished from desire? The failure to want sensibly is a failure of disentanglement: a pathology sets in in which desire cannot be penned up inside limits, in which need infects itself with wanting and the streams cross irretrievably. This torment, such as it is, generates its own twisted form: the anxiously attached and scribbling lover, halfway between a visionary and a child, frantically willing herself back into the forgivable, imperious demands of infancy.

*

A few weeks after the graphomania had set in, ‘the woman’ who worked in the university had to face, as I have to face now in writing this, the transition from ‘the woman’ to me. To act on desire, to feel it reciprocated with some force, roots you in yourself, your ‘I’, whilst simultaneously opening up its boundaries: not only to the other, the desired other, the object or whatever you want to call it, that you have let in, but also to the rush of all the other first-person-lovers that come flocking into you. Which is to say, she got what she wanted.

The next day, on very little sleep, she had to take a train to London and read poems at an event celebrating the first collection of poems by V. R. ‘Bunny’ Lang, a poet who died tragically young, aged thirty-two, of Hodgkins Lymphoma, and who was affiliated, vaguely, to the emerging New York School. Rosa Campbell, whose labour it was that unearthed and patiently brought Bunny out into the light, writes in her introduction to the book, which is called The Miraculous Season, that

You probably haven’t heard of Bunny Lang. Or, if you have, it’s because you’re a Frank O’Hara fan, and can recall poems dedicated to her: “V. R. Lang,” “An 18th Century Letter,” “A Letter to Bunny.” Or perhaps you remember the sudden shift in “A Step Away From Them,” when O’Hara pivots from the joys of cheeseburgers, Coca-Cola, and hot shirtless labourers on the streets of Manhattan to the lines: “First / Bunny died, then John Latouche / then Jackson Pollock. But is the / earth as full as life was full, of them?” To learn that someone has died before you’ve even been introduced properly seems unfair—to you, to them.

In gathering together in a bookshop in London to read Bunny’s poems aloud, the group were resurrecting her a little, trying to redress the balance. They were bringing Bunny back to her body and to her voice, which, on the page, is so singular: in the words of Eileen Myles, ‘it’s like she just walked in’. (O’Hara, in ‘Letter to Bunny’: ‘When anyone reads this but you it begins / to be lost. My voice is sucked into a thousand / ears and I don’t know whether I’m weakened.’). The woman had read through the book, revelling in the distinct Bunny-ness of Bunny, a few weeks beforehand, and selected the poems she wanted to read. She didn’t reread them before the event, discombobulated as she had been by what had happened the night before and by her persistent hangover. So, when she turned to the page she’d marked and began to read, she found herself blindsided. This wasn’t Bunny; it was her. The poem had written itself into her, or vice versa, without her realising, and now she had to stand up amidst the new releases with a half-empty Asahi in her hand and reveal to everyone there what was going on underneath her skin.

The poem, which is untitled, goes like this:

I waited five hundred centuries for the White Crow

I waited IT CAME IT FLEW AWAY

They that told me it would come forebore to tell me

That it could leave me this way,

More desolate than I ever was

Isolated out of all proportion

Moaning, when I am alone, in no language

Howling like an animal.

Now, on my knees for some reason—

Clawing my face.

I am like this. If I had known,

I would not have waited. Even listening

To the remembered roar of wings and

The explosions of those first planets which

Screamed going past like eagles

Even still tasting that salt

On my lips my cheeks Oh Jesus, down my knees

Mumbling your name, mumbling your name

The voice wills itself into obliteration. It waits for ‘it’ to come; it wills it away, it breaks its own utterance down into a mumbling and a screaming. ‘It’, I think—the ‘White Crow’—is neither need or desire but rather a third thing: the force created when they can no longer be distinguished from one another, when they combine in an object so loved, so wanted, it demolishes its beholder. But this space in which language obliterates itself—is obliterated, perhaps—is also one in which ‘no language’ is spoken into existence. Howling, moaning, screaming and mumbling, the graphomaniac’s hand moves fervently on beyond the dismemberment of her body.

Freud, in his 1908 ‘Creative Writers and Day-dreaming’, makes a direct equation between the creative writer and the ‘child at play’: the play is serious fantasy, but it remains separate from reality; the mark of healthy adulthood—in this account, anyway—is the fierce privacy of the boundaries within which these fantasies are kept. It is only neurotics, he tells us, who the ‘stern goddess – Necessity’ has ‘allotted the task of telling what they suffer and what things give them happiness’. D.W. Winnicott conceived of it differently: in his theorisation of play in 1971’s Playing and Reality, the child at play is engaged in the complicated construction of the self—including using transitional objects—which negotiates an intermediate space between the inner and the external world: ‘the intermediate area of experience, between the thumb and the teddy bear’, which is also, crucially, an area ‘between primary unawareness of indebtedness and the acknowledgement of indebtedness’.

This, of all the hundreds of pages Winnicott published on attachment, was the part of his oeuvre which struck Barthes: in A Lover’s Discourse, the lover is defined by the condition of waiting, but ‘the being I am waiting for is not real. Like the mother’s breast for the infant, “I create and re-create it over and over, starting from my capacity to love, starting from my need for it”: the other comes here where I am waiting, here where I have already created him/ her. And if the other does not come, I hallucinate the other: waiting is a delirium’. In the copy of Barthes’ book that I read, I’m reading a translation into English of Barthes’ quoting of Winnicott in French. I prefer the way Winnicott phrases it in the original, including its—ironic in this context—opening acknowledgement of the need to rephrase: ‘In another language, the breast is created by the infant over and over again out of the infant’s capacity to love or (one can say) out of need. A subjective phenomenon develops in the baby, which we call the mother’s breast’. For Barthes, a subjective phenomenon develops in the lover: the anxious state of waiting is a ‘pure state’ of loving. For the graphomaniac, the subjective phenomenon that develops is one of address. The addressee of her frantic annotations is not the man she is writing them towards, but rather the gap between needing him and wanting him—the idea that she could somehow write so much, tap-dancing across a vista of earlier loving texts, that she could close it, compel him, by her own compulsion, to climb the stairs up to her office/bedroom and give her, finally, the relief of something else to think about.

In Bunny Lang’s poem, whether or not the waiting of the lover—five hundred centuries of it—is a delirium is beside the point: it’s the being left that can’t be borne. In order not to be left, the speaker must wish for the loved one not to come, but if she could manage that, she wouldn’t be in this situation in the first place. Lang, by writing a poem, creates a space in which the fantasy is both public and private at once: her intermediate space climbs into the reader’s own throat as they read it. The waiting is at once waiting and not-waiting, the wanting is both wanting and wanting to not want: it’s the fort/da of ambivalent attachment, spoken into printed being with such a force it splits apart its own language. Go away, come back.

*

Let’s return to our graphomaniac: standing, as if naked, under the glare of the bookshop lights. What is it that makes her symptoms so morbidly persistent? What is she scared of? What does she believe she is waiting for?

Death was on her mind, that’s true. Bunny’s death, just a year older than the woman was at this time, scared her, because dying scares her: she does not want death to happen to her. A kind observer could say, to excuse some of the wilder reaches of her own behaviour during this period, that she was acting out against death by seeking the fulfilment of her desires: she was in the grip of a minor health scare, it’s true, with an approaching biopsy weighing on her mind. But that would be a convenient obfuscation. For a hypochondriac who is morbidly afraid of dying, health scares are peculiarly vivifying: they bring her back to herself, they regulate her usual state by assuring her that she’s not crazy, that there is—thank God—something to worry about, that life is, indeed, hideously finite.

Writing is some form of ballast against the grave, especially writing that ends up published, living on in public long after the demise of the voice and the hand that formed it: Kundera’s definition of graphomania might prompt us toward this diagnosis. It’s true that, in the book that the graphomaniac annotated, Gillian Rose is at the end of her life, shoring a final piece of her voice up against the oncoming silence. The book, which is called Love’s Work, includes a passage in which Rose, a philosopher who took language as seriously as it is possible to take it, declares that

However satisfying writing is—that mix of discipline and miracle, which leaves you in control, even when what appears on the page has emerged from regions beyond your control—it is a very poor substitute indeed for the joy and the agony of loving.

She then goes on to imagine the spurned lover as a child or as a dog:

Imagine how a beloved child or dog would respond, if the Lover turned away. There is no democracy in any love relation: only mercy. To be at someone’s mercy is dialectical damage: they may be merciful and they may be merciless. Yet each party, woman, man, the child in each, and their child, is absolute power as well as absolute vulnerability. You may be less powerful than the whole world, but you are always more powerful than yourself.

Love in the submission of power.

This ‘joy and agony,’ then, depends on the relinquishing of control, and particularly on the control over the subconscious or unconscious desires that writing itself allows you to marshal, filing them up and ordering them neatly into sentences on the page after their emergence ‘from regions beyond your control’. Barthes agrees with Rose, as it happens: in a line which mirrors her declaration against the possibility of a loving democracy, he writes that

There is no benevolence within writing, rather a terror: it smothers the other, who, far from perceiving the gift in it, reads there instead an assertion of mastery, of power, of pleasure, of solitude. Whence the cruel paradox of the dedication: I seek at all costs to give you what smothers you.

We can assume, though, that these kinds of writing are public: both Barthes and Rose are, at the point at which they’re writing these books, veterans of many publications (Barthes, too, was close to death—though his, courtesy of a laundry van, was a surprise). How can we account for the private writing of a graphomaniac in this theorisation of submission and control? What she is smothering, strictly speaking, is Rose’s text: imposing her own structures on top of it, forcibly breaking its enclosed boundaries of reference and deciding, no, actually, you might think this isn’t about Così Fan Tutti and Daniel Deronda, but I say it is. Perhaps to give such an artefact to the desired other is a form of exerting control not over the lover but over desire itself. Barthes uses the word ‘mastery’—or rather, in French, he uses the word ‘maîtrise’—and in Rose’s example of the dog we also hear the ghost of a master.

But the feelings of the graphomaniac, the feelings she found reflected back to her in Bunny Lang’s White Crow, are not to exert mastery over another: rather, she wants to submit to somebody else. To make such an approach in public life is risky at best. But in the margins of Rose’s text? Cloaked safely inside the pretence of having already written these annotations, a long time ago, with nobody in mind? Here the need to relinquish control can express itself in the reperformance of the control she exerts as she annotates a text about desire, power, love, and submission. Here, she can be the owner and the dog, the infant and the breast.

Kostenbaum, in his account of logorrhea, borrows words from Emily Dickinson: it is the ‘infection in the sentence’, a sentence ‘that breeds and germinates’. He continues:

The sentence - or the word - breaks open, and more words, more sentences, crawl out. Call it cloning, or festering, or spontaneous generation, or infection, or panic, or incest: it is the structure of autobiography.

Dickinson, though, did not write autobiography. Enclosed in her cloistered life in Amhurst, writing frantically and for the most part desperately privately—only ten of her nearly two thousand poems were published in her lifetime—she fits better the role of the graphomaniac than the logorrheic autobiographer.

Of all her work, this is most true of the so-called ‘Master Letters’. Simultaneously her most private, her most compulsively revised, and her most ambivalently addressed, there is no evidence that these letters, all addressed to a man (apparently, anyway) she called ‘Master’, were ever posted. Dickinson’s hand has been the key to decoding their date, if not the identity of such a fervently submitted-to other: from shifts in the lower-case form of her handwriting, especially in the word ‘the’, the order of the sequence of the three letters is now thought to be spring 1858, early 1861, and, finally, the summer of that year. (When a heavily edited version of one letter was published by Mabel Loomis Todd in the edition of Dickinson’s letters she brought out in 1894, the address to the ‘Master’ had been removed, replaced with “To ––– –––,” and an intentionally misleading date had been assigned, some twenty years after they were actually written).

The Master Letters are so heavily revised that reading the typed edition of them feels like reading a musical score. Here’s part of the first letter:

I cannot 〈talk〉 ↑stay↓ any 〈more〉 ↑longer↓

tonight ↑〈now〉↓, for this pain

denies me –

In the second letter, Dickinson has revised it several times with different pencils, and in the third, there are a mixture of revisions in pencil and pen. Reading the editor’s notes to these revisions creates a curious sense of vertigo, and the precision with which the changes to such a pitch of fervent and unsettling desire are described is almost bathetic: ‘On the first page Dickinson neatly reworked “He” into “I dont” so that the change was inconspicuous, and on the third page, for clarity, she touched up the “e” in “breast”’. In these letters, Dickinson pleads with her Master, imagining herself—who she refers to as ‘Daisy’—coming to him ‘in white’, imagining herself as a bird with a gash in its breast. The letters are fantasies of punishment:

〈now – she〉 Daisy 〈stoops a〉 kneels,

a culprit – tell her

her 〈offence –〉 fault – Master –

if it is 〈not so〉 small

eno to cancel with

her life, 〈Daisy〉 she is satisfied –

but punish – do〈not〉nt banish

her – Shut her in prison –

Sir – only pledge that you will forgive – sometime –

Dickinson/Daisy wants only absolute obliteration: she wants to be told her offence and offer her ‘small’ life to cancel it out; she doesn’t mind imprisonment, she just can’t bear to be banished, to be apart from her Master. And yet, she was, doubly: apart enough to warrant the composition of the letters in the first place, and even further removed if, as it seems, these texts covered in scrawling revision and re-revision, were never sent to him. The Master Letters are the graphomaniac’s domain, where need and desire—distinction between them collapsed—construct a condition of ecstatic waiting: the submission is offered, the request is made for domination, and the paper buckles under fantasy’s weight.

Master – open

your life wide, and

take 〈in〉me in forever,

I will never be tired –

I will never be noisy

when you want to be

still – I will be 〈glad

as the〉 your best little

girl – nobody else will

see me, but you

The promise Dickinson is making cannot be fulfilled, but the impossibility generates the desire. In writing out what she wants, she returns to the creative possibility of childhood—‘I will be / your best little girl’—but a state in which the sublimated or pre-conscious aspects of erotic life are freed from their own latent prison, redrawing the lines of obedience and submission as something powerful even as they subordinate the agency of the self.

*

Let me now outline an imaginary postscript.

What if we found out, years after our analysis has concluded, that the graphomaniac once received, some years before the events in her workplace, a love letter in the post. It was many pages long, handwritten, sent with an urgent feeling from a man she had known since her childhood, whom she perhaps loved, and whom she had been avoiding ever since they finally crossed the boundary between the platonic and the not. She knew what was in it; she burnt it. They did not speak for another seven years: in the interim, he got married. (A marriage vow is the opposite of the graphomaniac’s scrawl: the ultimate speech act.)

An obvious answer to the riddle: all her compulsive writing is belated, a way of clawing back. But it’s not so simple. She wanted the book back: she got it.

Click here purchase the issue in which this piece originally appeared, or subscribe to receive all future issues as soon as they're published.

You can subscribe to our infrequent newsletter here: